Ways Machine Learning Has Shaped My World View

28 May 2022Embedding Vectors are Internal Representations:

Many concepts fit well into an embedding space analogy. Music genres, let’s say, are loosely defined categories that bleed in and out of each other through tractable and intractable connections. Representing them in high dimensional space captures there properties and bodes well that our embeddings are something like that is happening in our heads. All the ways embedding vectors inform me requires a youtube video and some sketching, but it suffices for now to recognize that we too have internal representations that compromise the essence of ideas but not the whole thing.

When you’re reminded of a song but can only recall the colors of the album cover? You’ve recovered parts of that internal representation but not the whole thing. When you’re competing in an physical game like basketball or ultimate frisbee and you’re doing lots of processing but only seeing bits and pieces of the information in your mind? You’re operating on lower level internal representations because your brain needs to act more quickly and doesn’t have the time to propagate them up to the fuller, richer representations. When something someone says reminds you of something which leads you to something else and then one more step yet none of the individual steps were fully formed or complete sentences or total explorations of the ideas? You just needed to touch on the internal representations and they led you on and on to another point. You didn’t need to surface it all the way to the top and pick it apart in detail. That’s what makes the representations so powerful.

In humans, these internal representations can be tracked to experiences and feelings. We both can feel and are conscious of individual parts of our cognition.

Loss, Pain, Reward, and Joy

ML algorithms adjust themselves based on signals like loss or reward. Loss is minimized and reward is maximized, and you generally are optimizing for one or the other. We can fiddle the numbers that define our algo up or down with respect to our current optimization goal using calculus (this is the essence of machine learning). I’m not focusing on the algorithm that chooses the actions here, I’m focusing on the loss and reward itself, and moreover that for us humans, loss and reward are feelings.

Instead of ‘you checkmated the opponent’s king, here’s a reward of one,’ it’s ‘you checkmated the opponent’s king, you feel elated and triumphant! nice’. Instead of ‘you guessed the wrong word and so your loss has an extra .25 magnitude to it,’ it’s ‘oh fuck oh shit that was the most embarrassing thing I’ve ever said I’m such an idiot oh fuck.’ I haven’t been that embarrased since middle school BUT the internal experience that is that loss. It’s painful. It’s to be feeling like that because it needs to be.

The overall point I’m trying to communicate is that these things that happen internally are to be monitored. “Pain” in our head as loss/reward is easy to handle, but furthermore all internal experiences are some part of cognition, and understanding everything’s place within your personal cognating system will help you deal with and shape that system.

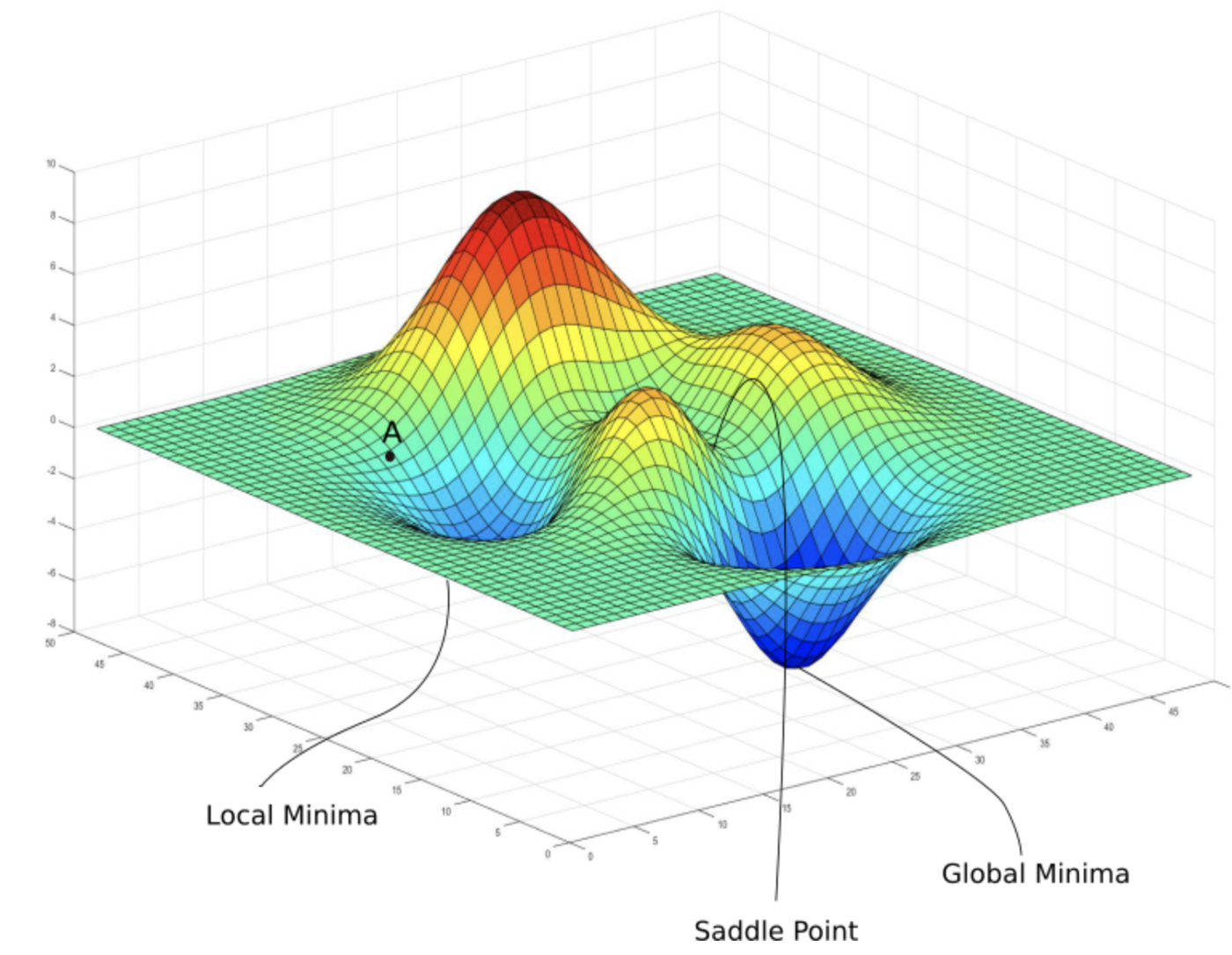

Local Minima Keep you Trapped

You want to get to the lowest point on a plane, but you arrive at a low point that is the lowest in its area but not the lowest on the entire surface. When you’re sitting at that local minimum, every direction from where you are is a step up, despite your goal of descent, so it appears that you’re at the best spot. In order to get to the global minimum, you need to somehow realize that taking those apparently bad steps are actually the correct thing to do.

After deftly mastering the concept of loss approximately two paragraphs ago, I’m sure your mind is thinking something like ‘aha! that applies to the loss landscape! at the bottom of one of these local minima, it appears that any small change to the model would result in worse performance, even though there is better performance farther away!’ Phenomenal insight you’re having. How does it translate for humans?

After deftly mastering the concept of loss approximately two paragraphs ago, I’m sure your mind is thinking something like ‘aha! that applies to the loss landscape! at the bottom of one of these local minima, it appears that any small change to the model would result in worse performance, even though there is better performance farther away!’ Phenomenal insight you’re having. How does it translate for humans?

This analogy impresses me as it keeps coming back to show usefulness in new ares. When learning a skill, you might have to break out of previously learned patterns that weren’t as expert as you thought. From your starting point, that seems wrong as you’ve learned them to be correct, but once you master the advanced technique, you’ll be out of your local minima and performing better. When in a certain phase of life, you have learned a pattern and get ingrained into it. I’m thinking cycles of the week and what you’re pursuing daily after work.

Train/Test Set Difference Shows You What Learning Is

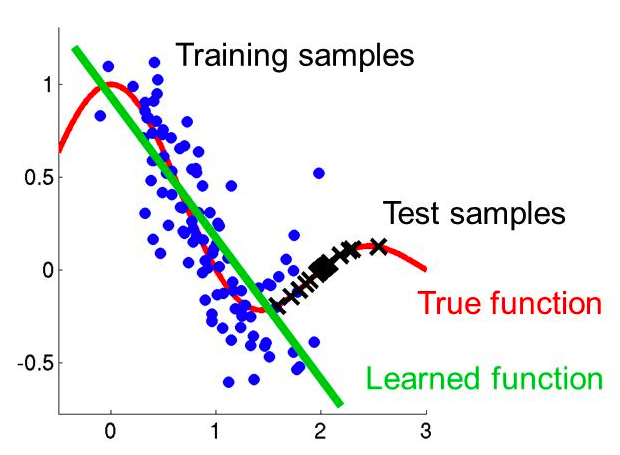

Let’s say you train a model to detect dog or no dog in a photo. You train it on pictures of dalmatians, then feed it a picture of a golden retriever. Likely, it has learned only the patterns of dalmatians and will not recognize the golden retriever. You did not expose the model to enough of the ‘true’ data distribution to model the full problem. If you see the picture below and understand how ‘all dogs’ are the ‘True function’ and how the training set of only dalmatians misses out on the whole distribution, you’ve gotten what you needed.

An illustration of an incorrectly learned distribution based on the difference between the data that was used to derive the function vs what it was applied to. The training examples are the blue dots, the test examples are the x’s.

An illustration of an incorrectly learned distribution based on the difference between the data that was used to derive the function vs what it was applied to. The training examples are the blue dots, the test examples are the x’s.

We, too, are products of our experiences. We all have our individual training sets, and how we act is inescapably based on those experiences. Every act we take is a product of how we’ve learned. I hope this tweet puts this in human terms:

some people identify as “I’ve always been honest” bc they’ve always been made to feel honesty is safe for them lol

— Ava (@noampomsky) June 13, 2022

The second useful paradigm in here is that intelligence is a function. f(x) = y, where y is the output and x is the input (input being sensory inputs, the current state of a game, or the previous thing someone said in a conversation). Take the red line and green lines from the example above. The whole idea of learning is adjusting the green line to be as close to the red line as possible, but you can’t see the red line, you can only see the data points that are the red line + a bit of noise in each data point which pulls it a bit off of the red line. This is my central definition of what it means to learn.

Skill vs Wisdom vs Intelligence

I was once watching Hikaru Nakamura, a top five supergrandmaster chess player, stream some blitz chess (each player gets 3 total minutes for their moves, no increment). His opponent retreated his bishop and Nakamura recognized the position, played three or four positionally forcing moves, and entombed the bishop behind his opponent’s pawns. After the game he showed a classical match (120 total minutes per player with 30 additional seconds added every turn) he had played fourteen years before against a Mexican GM in which the same situation with the bishop happened. (I do not have a timestamp to the moment on stream sorry u have to trust me)

This story neatly demonstrates working definitions of skill, wisdom, and intelligence. Choosing the right moves was skill, it was achieved through wisdom, which was originally found through intelligence. The skill is the raw output. Actions are taken and they achieve the end goal or do not achieve the end goal, and how well you achieve that goal is skill. Wisdom is applying previous knowledge to the current situation. Hikaru had seen that board position before and it was wise to apply what he knew about it. Intelligence is your ability to process a new situation. Way back when, assuming he hit that position in the game and then figured out what the best move was over the board, our streamer used his intellect to intake the board position and derive a skillful response.

These are not the widely agreed upon definitions from literature, they are how I’ve come to interpret the murky definitions that float about the field of machine learning. “Intelligence” is famously ill-defined, with notable attempt taking a solid sixty-four pages). Skill isn’t really officially defined and wisdom is far too human or artisitc of a concept for ML to have tried to pin it down yet.

Bonus: shape rotators vs wordcels

The impetus of “shape rotators vs wordcels” makes itself super clear when you’re familiar with ML and specifically embeddings. High dimensional representations are shapes. Manipulating these manifolds that define these representations in your brain is shape rotation. Words are the abstract concepts constructed on top of the interplay of all these shape. Wordcels play on the levels of the abstractions and the fallout of these abstractions and don’t come down and deal with the technical underbelly, creating the “shape rotators vs wordcels” dichotomy. Of course all people do both all the time, but the applicability as well as the ease with which it intuitively follows from linear algebra is kinda cool.